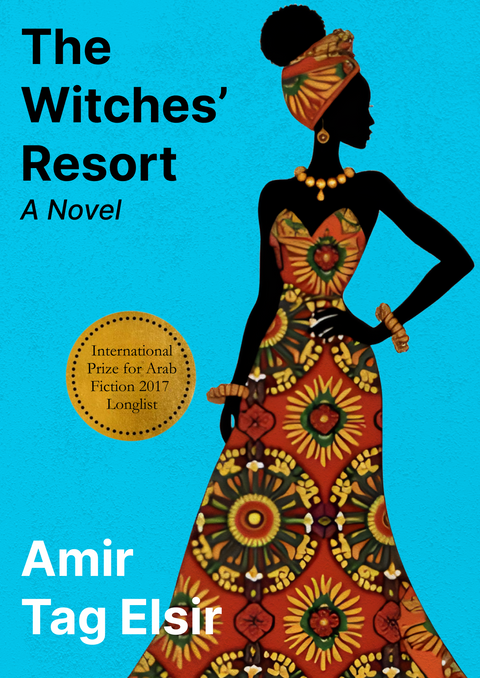

The Witches Resort

Read e-books on your Kindle or your preferred e-reader - click HERE to learn how!

Amir Tag Elsir, one of Sudan’s most acclaimed contemporary authors, is known for his evocative storytelling and keen observations of social issues and human nature. He is a winner of the Katara Prize, and several of his works have been short-listed for the prestigious International Prize for Arab Fiction (IPAF).

The Witches' Resort, long-listed for the IPAF in 2017, is a poignant yet darkly comedic tale of survival, love and longing, set against the harsh realities of displacement and life on the margins. Ababa Tesfay, a striking Eritrean refugee, arrives in an unfamiliar city in Sudan, friendless and destitute, seeking refuge from the war that has torn her homeland apart. Abdul Qayyum, a seasoned street thief, appoints himself her guardian, and in doing so, discovers a love that transforms his existence. Yet, as their fates intertwine, the city’s unforgiving streets conspire to challenge their fragile dreams.

The year was ordinary, like most years that come and go. No monumental events in the true sense of the word, no earth-shaking disasters with destructive spirits, no dormant or erupting volcanoes, no surprises capable of fundamentally transforming a deeply ingrained belief of a people—as if dictatorships might suddenly dissolve into rivers of democracy, as if inherent injustice might apologize to its oppressed victims, as if hunger might retreat,

shame might revive itself, or football crowds, usually indifferent to cultural matters, might be moved by a passage in a book.

We are in a place slightly removed from the shore, in a city that sits directly by the sea. Its residents call it "The Witches' Resort" for no known or documented reason. Perhaps it arose from a myth or fable, one of those stories people often pass down. Officially, in the land registry and property records, it’s known as "Auction Square."

The Auction Square was once a golden carpet of fine sand, enveloped in great joy during festive seasons. Various traps of livelihood were set to catch holiday celebrants, especially children. Rotating swings were planted in the place, along with flying balloon rides and the giant winged horse. Popular games spread about: sieves, soap bubbles scattered in the air, the covered dish with a prize guessed by participants, and target shooting at a circle drawn on a wooden wall with a cork-loaded rifle.

Habibullah the Beloved, the magician—a tall, limping, mysterious man with polka-dotted leather shoes, a long brown beard, and colorful attire resembling women's clothing—would arrive out of nowhere. He would take center stage in a green cloth tent, crowded and noisy, with a black devil's face painted at its entrance, sporting multiple horns and fangs, beneath which was written "Keep Away." Inside, he would eat fire and sharpened razors, produce wild ducks and rabbits, colored turtles, and bulbs that glowed without electricity. His very short, extremely agile companion Sarsura would be split into two equal halves in a ritual both terrifying and captivating to spectators. Then he would vanish to places unknown, only to return in a new season.

Most puzzling about Habibullah the Beloved and his companion Sarsura was that they never changed or aged, despite appearing at festivals for more than twenty, perhaps twenty-five years. They had a big hand in the joy of three different days enchanting both the young and the old alike.

No one ever saw them in the city or any other city outside of festival seasons, from the time they first appeared until they disappeared for good. When the holiday rituals changed with the times, sweeping away all that was new and joyful, the Beloved and his slender companion vanished.

The joy was then limited to handshakes, the faint sparkle in children's eyes, and the automatic exchange of polite phrases like "May you be well every year" and "Wishing you safety and health."

The idea of transforming the place into an auction square came from investors who were fascinated by its size and loved that its location was so near the city center, with public transportation connecting to all neighborhoods. The plan was immediately implemented.

The torn or entirely absent shade was mended with climbing ivy and abundant neem trees. Fast-growing climbers were carefully planted, along with faded, heavy cloth tents that could provide shade and shelter for goods.

Cool breezes were improvised using water sprays from hoses connected to vehicles resembling fire trucks, and shallow buckets of water were brought from nearby creeks to further temper the heat. Within days, buying and selling spread as if it had always existed and not been recently ignited.

Buying and selling … more and even more buying and selling …

Caravans of living money came running from every inch of the city, settling into the place and dissolving into its flow. What was supposed to be normal conversation only happened through shouting. The calls for trading various goods were made through screaming, sometimes with chaos and impatience. There was always fraud and deception, frequent fighting with and without reason. Blind extremes of hunger and satiety were evident,

along with the glands’ secretion of every kind of hormone.

Auction hustlers, some from right there on the coast, others from neighboring cities, from deep Africa and even more distant places, multiplied in the place. They exchanged valuable things for trivial ones, and trivial things for even more trivial ones. Lice and cockroach pesticides, deodorants, face moisturizers, empty sacks, pollen grains, female fertility stimulants, and male enhancement pills were all on offer. Old public service vehicles, long retired from work, found buyers to support them and hold their hand in their final days.

During that period, certain individuals in society shone in ways they never would have without their dangerous auction talents, to the extent that they became stars surrounded by halos of light, pursued by rumors, tax officials and zakat offices like shadows.

Ibrahim Abdullah, shone as a specialist in watches and cameras, and so did Shaaban the Laugher, who was originally a fisherman. Others like Tik-Tik, Ibn Al-Naml, and Al-Shaitan Al-Rajim—former football players—gained more renown in the auction trade

than they ever had on the field. Nearly rising to prominence was Marbouk, the first woman to use her seductive, soft voice in bidding. Her success was cut short when a tongue tumor afflicted her, forcing her to withdraw and disappear.

It wasn't strange at all to find a thief who would rob your house at night and sell you your own stolen goods during the day, or to see a beggar whom you'd encountered dozens of times and given charity to out of sympathy, now shouting offers for Australian lamb, a Bristo pressure cooker, or a Vespa or Yamaha motorcycle, claiming he wanted to exchange them for cleaner, shinier ones.

It was said that poor patients from the general public came carrying hospital beds and blankets they'd been using in the large government hospital to sell them there. A midwife from the women's and obstetrics department was arrested for trying to sell an illegitimate baby she had taken from a young mother – a high school student who had delivered hastily and fled one night.

Those who witnessed the peak of the auction era would never forget the day when Captain Dashdash, the renowned navigation expert and commander of the national ferry Gordon Pasha, found his precious, long-lost prescription glasses being sold at an auction for a price that no one would charge even for a beggar’s glasses.

And how the old Mozambican traveler, Namato Kija, who visited the country once and made a brief stop at the auction square, cried out in amazement when he saw a medium-sized wooden Buddha statue, carved by his wife forty years ago, with her name engraved on it, on sale with a cheap antiques dealer who had never heard of Mozambique, Buddha, or the wife of an old traveler whose hobby was carving statues!

In those days, the national currency commanded great respect and dignity. Even the common copper coin carried formidable purchasing power, and everyone—from beggars and daily laborers to heads of government—heeded its resonant voice that echoed in the farthest corners of the earth.

One year, as travel from the city to the capital and other cities increased with the growing population, the old location became too cramped. New paved roads stretched out, and the small station near the city center could no longer contain the chaos—the fights, curses, thefts, kidnappings, conflicts, sexual harassment, and lost children. The local authorities found no better solution than to convert the auction square into a bus terminal.

The neem trees and climbing ivy were abruptly dismissed from their shade-giving duties, brutally uprooted. The gentle breeze was roughly stripped of its softness. The noise of buying and selling was replaced by the clamor of travel. Golden sand mats were replaced with tons of asphalt. The long-established auctioneers were evicted. But those who had settled there refused to leave voluntarily. They gathered, seething with anger, until they were forcibly removed by police wielding rubber batons and tear gas. Those classified as leaders of what was officially called the Auction Square Rebellion and popularly known as the Witches' Resort Uprising were arrested and later tried harshly.

Buses from brands like Tata, Bedford, Vauxhall, and Mitsubishi, and open-top four-wheel-drive vehicles modified locally into buses, arrived. Ticket booths were constructed from wood, white brick, and tin. Directional signs and travel indicators were plastered on walls and columns, creating new clamor against the backdrop of old noise, to the extent that people later forgot what existed in that old square, which was still called the Witches' Resort despite its dramatic transformation.

Near the ticket booths sat Hawwa, Saeeda, and Sayedat Al-Jeel—elderly, weathered tea sellers who had passed sixty-five long ago yet remained sturdy. They had rusty memories they tried to polish with occasional chatter. Their senses were no longer pure, sharp, or distinctive. Some of their children had died, some had migrated to work in Gulf countries or Europe, while others remained hungry at home or on the streets, waiting for food.

They were all born on the coast, in adjacent working-class neighborhoods that resembled each other in everything—from newborns' names to wedding ceremonies, circumcision rituals, and types of food, drink, and clothing.

They had worked at the old bus station since its inception, selling tea, and moved with the new bustle to the Witches' Resort.

They took great care in preparing tea, adding plenty of spirited spices, brewing it slowly and flavoring it with cinnamon, cardamom, mint, and cloves. They served it in green, red, clear, and patterned glass cups, accompanied by old laughter and traditional flirtation that refused to evolve into modern flirtation—perhaps beginnings of foolishness that would forever remain beginnings, never to be completed, but connecting them to the atmosphere of the public space.

Their tea connoisseurs were cut from the same cloth: employees, experienced travel drivers, driver assistants, regular travelers, aimless passersby, and unemployed folks who found some pleasure and excitement in the square, even if only through meaningless glances following female travelers, those bidding farewell, or women working in the area.

In the narrow wooden stalls roofed with dry palm fronds, people would typically relax with tea and coffee, taking brief respites from their journeys. Cheap local cigarettes—"Al-Baranji”—were very popular with the customers. Perpetually criticized topics like politics and football, problems that may or may not concern anyone, and dreams crushed before they were formed—such as migrating to Europe, marrying cinema beauty Sophia Loren, or gaining fame like the distinguished footballer Socrates—all took varying shares of attention.

The place was lively throughout the day, with crude insults frequently heard until late into the night. These would intensify whenever a city or capital football team lost to a rival, or when someone got ordinarily angry at another's ordinary anger, or when an obscure military officer suddenly overthrew a long-standing ruler in the early morning hours, as happened from time to time.

Sometimes, someone would get drunk on cheap liquor in Al-Saharij district—that distant part of the city's southern side, where illicit bars, worn-out prostitutes, and the unstoppable banjo drug trade thrived despite authorities' attempts to eliminate it— and then come to the place stirring up trouble or harassing women.

The role of the tea sellers was mostly neutral and cold: providing shade, flavor, and entertaining chatter, and witnessing for the sake of their livelihood if things escalated far. But things rarely escalated far, as their wings were soon clipped and their claws trimmed by intermediaries who entered with both good and bad intentions. The usual chaos would quickly return to the place.

The old auctioneers, who had scattered and moved their activities to a remote, untrodden part of the city with no transportation lines nearby, would occasionally visit out of nostalgia. They would ask, out of habit, about old wood, scrap metal, childcare services, or nothing at all. They would call out in their old way for scrap metal and non-existent old government vehicles.

Their nostalgia was met with laughter from the travel regulars. Their fat riyals would quickly dry up, and they would leave.

In that place, Abdul Basit Shajar, the official supervisor of the bus station, caused trouble several times. Most notably when he bit the ear of his Ethiopian teenage assistant, Nahum Arja, when the Al-Nujoom football team defeated their rival Al-Sho'la team, which he supported in the local first division league. The teenager had defiantly worn the winning team's jersey—a soft tulle yellow shirt decorated with red stars.

He bit his assistant's ear again when the boy claimed one day that Abdul Basit Shajar was his father.

And he bit it a third time on that memorable day when his dreams of marrying a woman who had unintentionally aroused his desires collapsed—he being an elderly widower over sixty.

In the same place, Abdul Basit Shajar also broke down, struck by a rare and difficult-to-cure fever of filth. No one knew where he caught it, but he recovered and returned as master of the place.

In the same place, the eyes of Abbas Salem, the health worker responsible for spraying pesticides—nicknamed “The Dead” because he had once died and awakened before burial—became accustomed to swelling and pumping blood whenever the regulars embarrassed him by talking extensively about his love for female goats, with whom he allegedly had “relationships”.

In the same place, the dervish, a friend of the underworld who appeared and disappeared, a former minister as he claimed, a collector of silver and gold coins and a healer of depression and sadness when needed, fell for the last time, never to rise again.

One day, a flood of laughter swept through, and another day, a flood of tears.

Secretly and openly, fortunes that were never gathered were divided, some sins were declared forgivable, and some unforgivable, and some repentances were announced that might be accepted in society or remain lost without acceptance.

Virtual rulers unknown to anyone were imposed on poor third-world countries, quick marriages were contracted and dissolved, and the love story that matured between Thuraya - a plump, dull-eyed madwoman who had always stayed in the place and then disappeared - and the strange, romantic bus driver, Saleh Salah, who ended his own life, bewildered by the strange world that lay hidden under her madness. These were the wonderful stories that abounded in that place that people will never forget.

***

“In the name of Allah, the Most Gracious, the Most Merciful”

“There is no power nor strength except through Allah.”

“O Allah, send blessings upon the beloved chosen one.”

“Amazement and awe... “

“Walk on, and may God's eye watch over you,”

"Girls are biscuits... Girls are candy... Girls are honey," and so on.

Many phrases, big and small, old and modern, bare and modest, were crowding the place. Some were written on the backs of buses, while others were still projects in minds, bound to be written later.

What the workers at the station truly prided themselves on was what they called "the good grace" - that the exhaustive investigation by those concerned there never revealed any undercover security officer appointed by the authorities to write reports about people.

All those suspected and interrogated by the concerned parties turned out to be genuine security men who came only for entertainment, far from any official assignment.

But the Eritrean Ababa Tesfay, the beautiful refugee, the homeless one, appeared out of nowhere.

Perhaps she was the right girl in the right place. Perhaps the wrong girl in the wrong place. Or perhaps neither this nor that. Just a beautiful, homeless refugee girl who came one day.

- Society & culture

- Drama

- Romance